Global Race for Electric Car Components is Threatening Indigenous Peoples in Indonesia

Indonesia, eager to benefit from the global demand for nickel, appears to be ignoring the social and environmental impact of mining it

Tupa does not know how old she is now, as the concept of birthdays is unfamiliar to her indigenous community, the O Hongana Manyawa. However, many of Tupa’s relatives believe that she is more than 70 years old.

The O Hongana Manyawa, which means "forest people," in their indigenous language, are one of the last remaining nomadic Indigenous Peoples in Indonesia. They are divided into 21 different bands, according to biologists B. J. Coates and K. D. Bishop, who spent time in the region as research for their book, Panduan Lapangan Burung-Burung di Kawasan Wallace (2000).

Tupa’s band lives within the Akejira forest in Central Halmahera District of North Maluku in Eastern Indonesia and is the smallest of the six remaining bands still practising the traditional nomadic lifestyle, which mirrors the migratory patterns of animals and the growing seasons of forest fruits.

Her community often faces discrimination due to perceptions that their lifestyle is primitive and backward. Now, however, they are facing a new threat – massive, multi-billion-dollar nickel mines and smelters encroaching onto their lands.

“Trees are gone and replaced with the big road, where giant machines go in and out making noise and driving the animals away,” Tupa said. For her, the forest is more than just a provider of food and shelter; it is also a home, and “the bridge” for all O Hongana Manyawa to connect with the spiritual world.

Tupa's band and their traditional way of living are threatened by the PT Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park (IWIP), one of two mega-nickel integrated mining and smelter projects in Indonesia.

IWIP is the first integrated industrial estate in Indonesia which is intended to facilitate the mineral processing and production of electric vehicle battery components. During the 2.5 years since the groundbreaking, the investments made by the combined Chinese investors are worth approximately 5 billion USD and will continue to grow to 11 billion USD.

Traditional ways under threat

For decades, the Indonesian government has been trying to resettle the other 15 bands of O Hongana Manyawa outside the forest and force them to adopt conventional settled lifestyles, leaving Tupa’s as one of the few practising a traditional way of life.

The O Hongana Manyawa divide the forest into three categories based on how they use it, according to Syaiful Madjid, a sociologist from North Maluku Muhammadiyah University. Fongana or the residential area is where they build their huts, Ragi Maamoko or hunting forest is where they hunt, and Hongana Magogomana is the area designated for sacred rituals, where no clearing or settlement activities are permitted.

Since the mid-1970s, O Hongana Manyawa communities have been harassed and repeatedly accused of being perpetrators of violence within the Halmahera Forest, due to their hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

In March 2014, two male members of the Akejira band of the tribe were arrested under suspicious circumstances. “Bokum and Nuhu were both falsely charged with murder, regardless of insufficient evidence," said Munadi Kilkoda, the regional chief executive of AMAN (Indigenous Peoples Alliance of the Archipelago) in North Maluku. "It’s pure discrimination which has been going on for many years.”

Bokum, then the leader of the Akejira group, and Nuhu were charged with first-degree murder and were sentenced to prison for 15 years. Nuhu died in 2015, due to deteriorating health conditions after suffering physical abuse by the police during the interrogation process.

“When they arrested Bokum and Nuhu, I knew it was time for me to step forward,” Tupa said. Tupa and her fellow tribe members cannot speak either the local Malay dialect or Indonesian and have limited trust in outsiders. She believes that Bokum and Nuhu were arrested because of their refusal to give up the land to nickel company IWIP to be converted into nickel mining sites.

Now Tupa is leading the band, which consists of four women and three children. Bokum and Nuhu were the only adult men in the group, responsible for providing meat through hunting. According to Tupa, the forest regions targeted by IWIP are part of their traditional hunting zones and sacred forest areas for spiritual activities.

“When IWIP first arrived [in late-2017], we welcomed it,” Tupa said, recalling that the people who met with Mutia (then the band leader, Tupa’s late husband) and Bokum were smiling and laughing – signs perceived to mean they intended no harm. Much of the company’s initial message was lost in translation, and even when it began to be better understood, the O Hongana Manyawa people believed that they would be left in peace if they refused to cede their lands.

The IWIP representatives visited the band several times, bringing offerings of canned fish, coffee, sugar, instant noodles, rice and candy for the children. For Tupa, these gifts were simply customary, as visitors acknowledging the band’s rights over their territory. They were not accepted as tokens of agreement.

IWIP began to mine for nickel in the forest – which, to Indigenous nomads like Tupa, has been home for generations and symbolizes the existence of their community.

She is now focusing on how to feed her band members, since gathering food is much more difficult than it used to be.

The mockery of Free, Prior and Informed Consent

IWIP is the result of a combined investment of three Chinese companies – Tsingshan Group, Huayou Group, and Zhenshi Group – according to data compiled by AEER, an Indonesian-based social and environmental advocacy organisation. Tsingshan is the majority shareholder with a 40% stake through its subsidiary, Perlux Technology Co., while Zhenshi and Huayou own 30% each.

The project is divided into three stages. First is a US$2.5 billion development of ferronickel through pyrometallurgy smelters followed by a US$1.5 billion development of nickel and cobalt production in the form of hydroxide. The final goal is to be able to produce batteries for electric cars.

The scale of investment raised concerns from AMAN over the lack of a proper Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) process, a specific right recognized in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples allowing them to give or withhold consent to projects affecting them or their territories.

During a ceremony performed in 2018 to mark the beginning of the project, IWIP claimed that they had obtained community consent and that Akejira nomads had agreed to the nickel mining activity in Central Halmahera. In response to this reporter’s request for comment, Agnes Megawati, IWIP’s Head of Communication and Media Relations, shared an existing public statement which states that the corporation maintains good relations with members of the Tobelo Dalam Indigenous Community from the Akejira area.

AMAN is sceptical. “FPIC required the company to openly share all information regarding the project with the community so it could independently decide whether it would approve or reject the investment,” Kilkoda said.

“With language barriers and illiteracy, how can IWIP claim that it had properly obtained the community agreement?” Kilkoda said.

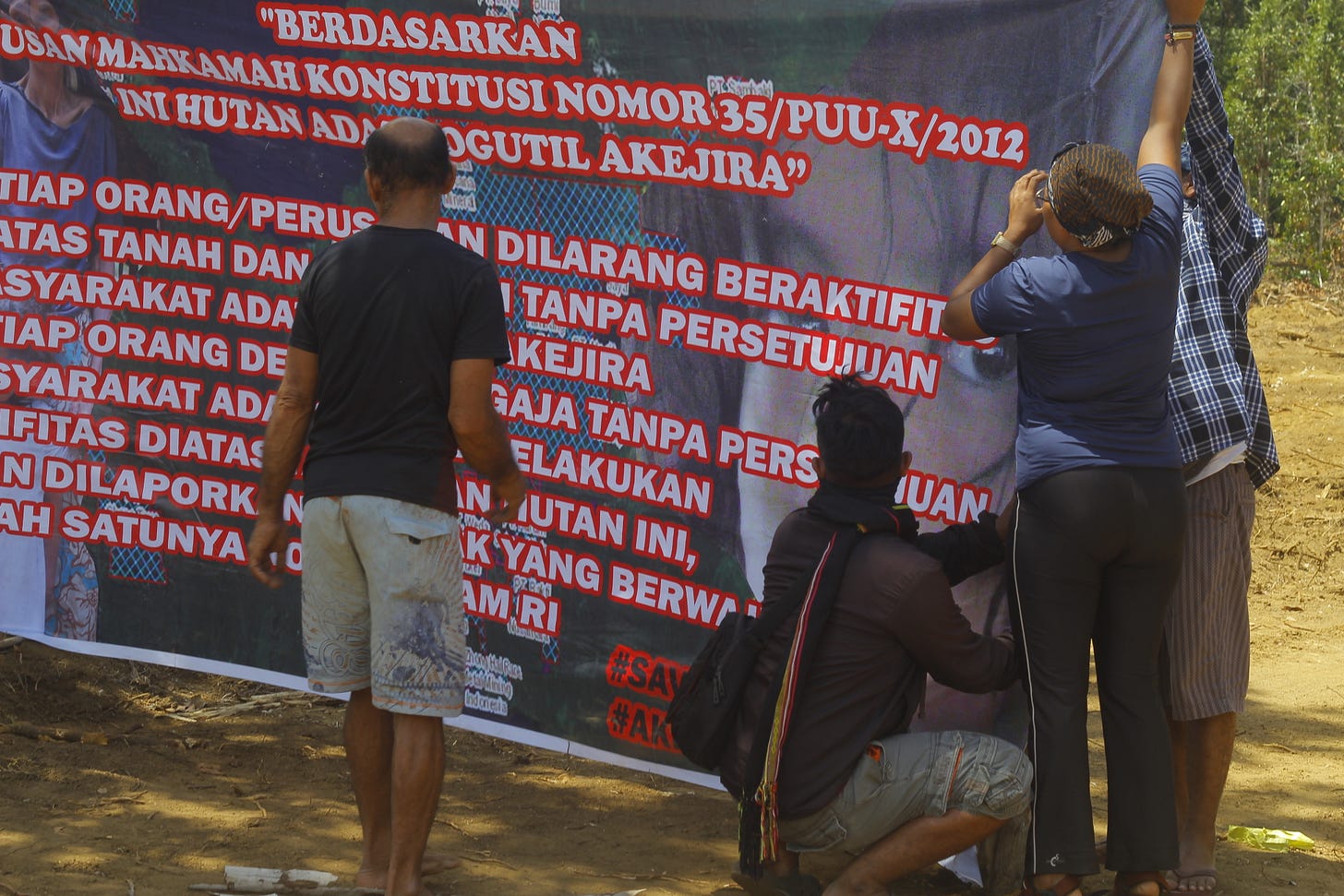

“Why do they still ignore the fact that the community has openly refused the project, notably after the latest forest clearing destroyed their ancestral tombs and cultural sites and poisoned the river?” he pointed out, referring to the series of protests in 2019 by the relatives of O Hongana Manyawa band who live in Akejira forest.

Kilkoda believes that this is more than enough to prove the absence of proper Environmental Impacts Assessment (EIA), and High Carbon Stocks and High Conservation Values (HCS-HCV) studies in the area, which are the basic requirements of a FPIC process. HCS and HCV are approaches used to identify and protect important environmental and social values that should be conserved.

However, the criticism has not slowed the Weda Bay Industrial Park, which proceeded with the construction of two nickel smelters. The first is run by Weda Bay Nickel, a joint venture between France’s Eramet, Tsinghan and Indonesian miner PT Antam, while the second is operated by Yashi Indonesia Investment, which is co-owned by Tsinghan and Zhenshi.

On its website, Eramet prominently promotes Weda Bay nickel as a “remarkable success story” of its cooperation with Indonesia in extracting nickel from “a far-flung corner.” The story, as told by the firm, is that Weda Bay Nickel is Eramet's testing ground for developing positive relations with stakeholders.

“Greg Cock, a thirty-year-old Australian geologist recruited by Strand, a small Canadian company, exits the helicopter (in 1996, the first time Eramet looked at Weda Bay). Surrounded by a swarm of jubilant youngsters, the bule, or foreigner, is taken to a rental house, where he will spend the next year building a forward camp along the beach in Tanjung Ulie, eight kilometers to the east… In these far-flung lands live the Forest Tobelo (O'Hongana Manyawa), small nomadic communities who, research suggests, either fled the Dutch colonies in the seventeenth century, or took refuge in the forest during World War II, when the Japanese occupied the region.

However, this idyllic picture is not the reality of local people.

Lack of transparency

Deforestation caused by mining activity has reduced the area’s ability to absorb rainwater, resulting in greater volumes of runoff flowing into lower plains. But when a massive flood hit the area around IWIP in August 2020, the office of the Indonesia Coordinating Ministers on Maritime and Investments Affairs quickly denied it was caused by a lack of proper environmental impact assessment.

At a press conference the next day, Septian Hario Seto, the deputy head of investment and mining, said a team would be sent to investigate the cause of the flood and provide the necessary information to the public.

“We are confident that IWIP has done the EIA study properly, and what happened over there now is not an isolated case. It has been raining in Weda for three days, so it’s normal to have such an accident,” Seto was quoted as saying in Tirto, an Indonesian news provider. However, there have been no further updates on the report, nor any information on when it is going to be released.

Luhut Binsar Panjaitan, the coordinating minister of Maritime and Investment Affairs, has repeatedly highlighted the importance of Indonesian nickel mining, and his confidence that the country will play a pivotal role supplying raw materials for electric car batteries.

“Indonesia is rich and has more than enough nickel reserves to match the growing demand from the international market,” Luhut told CNBC Indonesia in March this year.

However, Pius Ginting, the executive director of AEER, argues that nickel mining in Indonesia is still far from ideal.

“We have to ensure that the nickel mining companies will comply with all the requirements and standards to avoid future social and environmental disasters,” said Ginting.

Friends of the Earth (WALHI) Indonesia, a frontline NGO that focuses on advocating environmental issues, has criticized the government for its lack of transparency, particularly regarding the mining sector which poses serious threats to environmental sustainability.

Nur Hidayati, executive director of WALHI Indonesia, said that environmental issues are a common problem. “The government must begin to be open, in particular regarding related data and information, and must start to involve different parties, including the community who are directly affected by the mining activity,” she said.

Until then, the Akejira band of O Hongana Manyawa despair as the only home they have known for generations is under threat. Electric cars that do not rely on fossil fuels have been touted as a solution to global environmental problems. But if the cars are produced at the expense of communities and nature, then humanity risks jumping from a frying pan into the fire.